James Glickenhaus is not what you would call a bombastic individual. Observe him trackside: He cuts a stoic figure, monitoring the progress of his Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus racing machines from beneath the wide brim of a Western hat. Walk up and say hello at an auto show and he’s engaging, if soft-spoken. He will thank you for your interest in his projects, and you’ll get the sense that he really means it.

This is not to say that his aspirations are modest. Glickenhaus wants to take his team to Le Mans, he wants to win outright and he wants to do it with an American-built car of his own design.

No one will ever accuse James Glickenhaus of a deficiency of ambition, but this is quite obviously crazy. Isn’t it?

Glickenhaus, movie producer and director and son of a Wall Street financier, has not spent a considerable amount of his money on a quest—one that has stymied manufacturers with storied histories and vastly larger budgets—on a whim. Learn a little bit about what Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus has accomplished so far, and his moonshot starts to seem (at the very least) within the realm of possibility.

Get the guy to open up a little bit and you’ll find real fervor. You’ll start nodding along as he outlines his philosophy on cars: This guy gets it. So maybe it is a little crazy. So what? From now on, you’ll be pulling for him and his people, hard, as he tries. You have become another true believer in America’s last real privateer.

On SCG 001

Glickenhaus’ base of operations, car stash and shop is an an old beverage warehouse tucked away on a residential street in Sleepy Hollow, New York. (Yes, Sleepy Hollow is a real place, just up the Hudson from New York City; yes, it’s quaint.) Until SCG's new, higher-volume factory in Danbury, Connecticut, is operational, it’s also where the SCG 003—a race-bred, race-proven supercar that ran the Nürburgring in 6 minutes, 33.20 seconds in competition trim—is hand-built in small numbers.

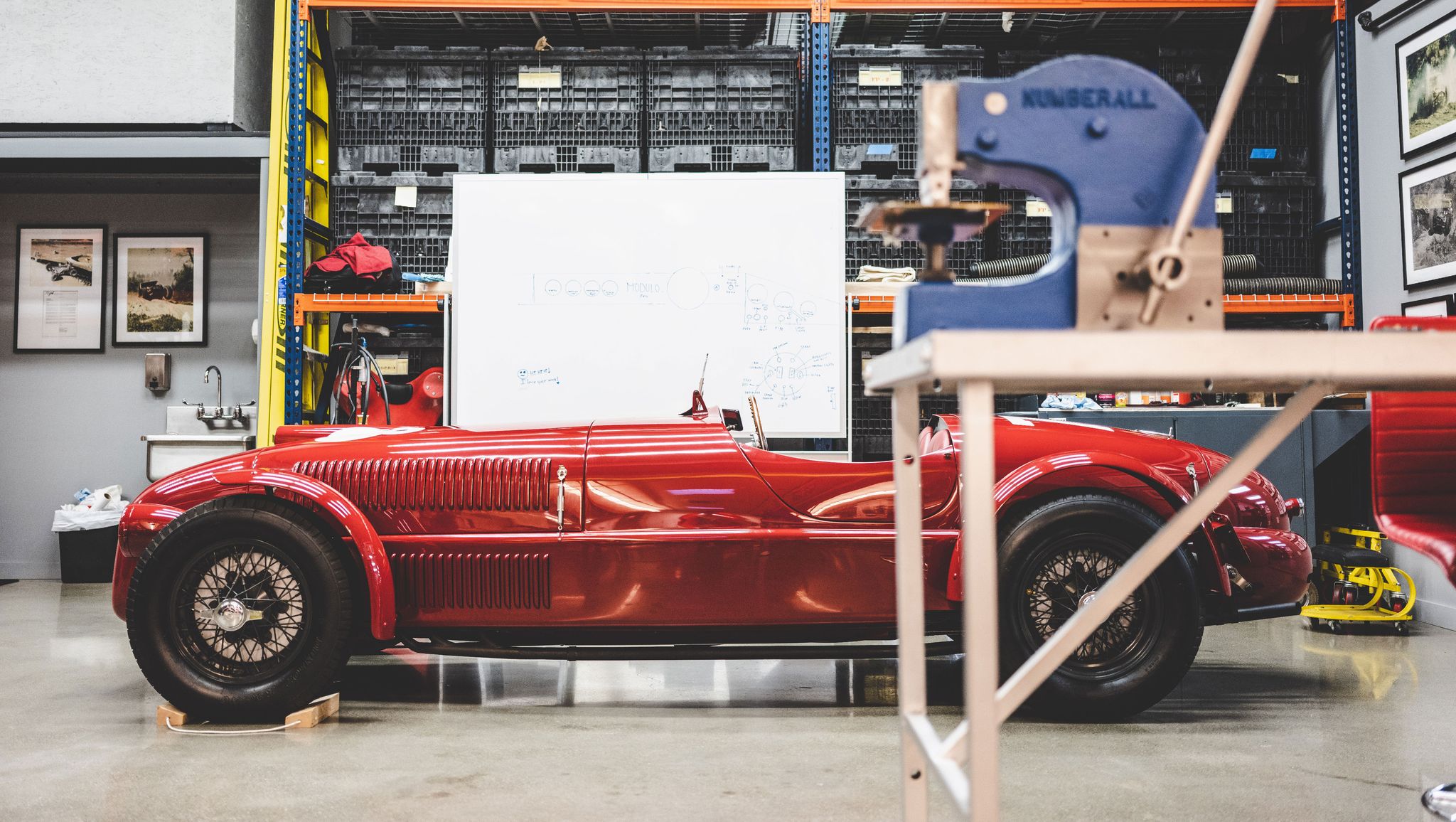

The bulk of the floor space is occupied by old cars, many of them race cars, a plurality of them Ferraris. Off to one side, his son Jesse is stamping out sample VIN plates for SCG cars on an old-school, hand-operated press. Serial numbers follow a little stamped rendition of the Statue of Liberty’s torch: the emblem of Glickenhaus’ automotive enterprise.

James points out interesting cars as we walk around. As it turns out, they’re all interesting, and there are stories to go along with each of them. Here is a 1967 Ford MKIV, highly original, still bearing a divot from an angry Bruce McLaren’s helmet. The tail of the car blew off during the ’67 24 Hours of Le Mans, in which it finished fourth.

A piece of that tail broke off and bounced into the stands. How did it end up in a display cabinet next to SCG’s racing trophies and concours awards? A French fan grabbed it, “and when he died about 40 years later, his kids found me on the internet and said, ‘You should have this.’ This shows you what the real violence of racing is. You go to Pebble Beach and the cars look like this”—he gestures to a pristine 1967 Ferrari 412P—“ but this …” he trails off.

“This is a Duesenberg owned by the Queen of Yugoslavia,” he says almost offhandedly as we pause at a Franay-bodied 1931 J. “She used real emeralds, diamonds and rubies in the dashboard; I’ll show you. See ’em sparkle? The hood ornament is really Lalique.” A while back he drove it to Jesse’s wedding in Newport, Rhode Island. Now it’s tucked—insofar as a Duesenberg can be tucked anywhere—beside a 1932 Stutz DV-32. It’s a little bit dusty.

Actually, most of the cars that aren’t actively being worked on or driven are covered in a thin layer of dust. It’s hard to explain why, but I instantly respect this. Maybe because this is a working shop, and Glickenhaus has better things to do than tickle his collection with a feather duster daily. Maybe it’s because the dust makes the near-priceless cars feel a little more real.

Off to one side is a blue 1966 Lola T-70 SL wearing subtle yellow pinstripes. It would be the centerpiece of a lesser collection; here, it’s hovering, wheel-less, on a rolling stand in an out-of-the-way corner. It has curious provenance. “This was a Donohue-Penske car that won eight major races,” Glickenhaus explains, “and it actually then went to Andy Warhol, who was going to use it in a movie,” which apparently never materialized. “And then I bought it. Look, I turned it into a hot-rod Lola; in those days, in ’72, nobody realized that the value of a race car was in originality. It was just an old race car.”

Which would be cool enough, but what Glickenhaus did later is illuminating. “This was the first Can-Am car that I drove on the road,” he says. Later, “after I’d made some money from directing The Exterminator”—the other cult-classic action movie about a pissed-off Vietnam vet thirsty for vigilante justice—“I basically modified it from a pure Can-Am car, which I did drive temporarily on the street, to what I consider the first SCG. It has air conditioning, windows that work. This is really SCG 001.”

On the SCG Philosophy

A few yards away is an SCG 003, the company’s hand-built $2 million-plus exotic. This car is in road-going configuration, but by design it can be converted to track use and back with relative ease. It’s powered by a motor based on Honda’s 3.5-liter turbocharged HR35TT IndyCar block, extensively modified by Glickenhaus and emissions-compliant. It has pushrod suspension and insane race car aero. It’s also fully road-legal.

In between the two, timeline-wise, is the P4/5 Competizione, aka SCG 002, parked on the other side of the building; more on that controversial car later, but for now, it’s interesting to note that—in a few very important ways—the SCG 003 has more in common with Glickenhaus’ hot-rod Lola than it does with the Ferrari-based, Nürburgring 24 Hours class-winning P4/5 C.

For one, it’s decidedly retro in conception, if not looks. “So our idea is, in the ’60s, you could buy a car, you could go to junkyard and get an engine. You could go to JC Whitney and get a kit that would mount it. You could put your Tempest 420 engine into your Studebaker and go drag-racing,” says Glickenhaus. “I want to go back to the day when a human being can work on their car.” Though SCG 003s might look like spaceships, “they’re modular race cars. The parts unbolt with Craftsman tools.”

The obvious question here is: If this is so self-evident to Glickenhaus, a comparatively scrappy operation, why can’t other manufacturers figure it out?

“It’s a conscious choice. Why, on our car, do we have Formula 1-style plywood on the leading edge of the splitter? Because when you drive these friggin’ cars, you prang that. So that’s sacrificial wood. It goes under the whole car, and it’s the lowest point. So when you bottom the car out, you’re hitting wood.

“Once a year, when you want to replace this”—inherent in this statement is the expectation that Glickenhaus clients will actually drive their damn cars—“it’s, I don’t know, $800 worth of wood. It’s not a $25,000 front splitter. Why don’t other people do this? I think it’s because they like charging you $25,000 for a splitter.”

If you can spend seven figures on an exotic car, you’re probably not too worried about the repair bills. With Glickenhaus, it’s about the principle of the thing. He wants his cars to be used. He knows enough about using cars on-track to know that they will break. So, he wants them to be easy and inexpensive—in relative terms, at least—to fix.

“I mean, I can show you a video of one of our customers augering in on the Nürburgring” in an SCG 003, he says. “He hit the nose, the tail, it was a huge impact. The car hit on three sides. We fixed that sucker in a month for 300,000 euros. If that was a LaFerrari, you would have thrown it in the garbage. I don’t know, we’re just different. It’s a different philosophy.

“I remember, I bought a Ferrari Testarossa, and the owner’s manual wouldn’t fit anywhere in the car. I called Luca”—here, he means former Ferrari chairman Luca Cordero di Montezemolo—“and said, ‘Luca, how can you sell a car with no place to put the owner’s manual?’ He said, ‘Oh, but our clients …’ and I said, ‘What, they want to put the freakin’ thing on a coffee table?’ Wouldn’t you want to know what the tire pressure is supposed to be? Wouldn’t you want to understand the car? Have any of these engineers driven these cars? I just don’t get it.”

On Ferrari

It is almost immediately apparent that Glickenhaus has a tremendous respect for Ferrari; it is not by accident that he wound up owning the 1947 Ferrari 159 Spyder Corsa, the third Ferrari built and the oldest Ferrari in existence (and the ’47 Turin Grand Prix winner to boot). But you also get the sense that it’s a complicated relationship; he is not an irredeemable tifoso. And projects like the P4/5 have gotten him into, at least for a short time, hot water with the often-prickly automaker (something about intellectual property and Ferrari's desire to control it tightly—it's a long story).

Still, it is probably fair to say that without Ferrari, there would be no SCG. “When I was a kid, I used to ride my bike from my parents’ house to Mr. (Luigi) Chinetti’s Ferrari dealership,” Glickenhaus explains. “Eventually he let me look into the window and come in. And what I learned from Mr. Chinetti was that you could take a sports car and turn it into a race car—it wasn’t like you had to build a completely different car. And in the ’60s, you could buy a Corvette, a Jaguar, an MG, a Triumph, an Aston Martin, a Ferrari, a Porsche. You could tape the headlights, drive to Lime Rock, race and come home.

“And the other thing I learned from Mr. Chinetti was that, as amazing as Ferraris were—and they were amazing cars—they could be improved upon. And NART improved them. They replaced the ignition wires, which were crap, with really heavy-duty hot-rod wires they bought at a speed shop down the block. And the last Ferrari to finish first overall at Le Mans was engineered and finished by Chinetti. It wasn’t a Ferrari works car; it was a NART 250 LM that won in ’65.”

Glickenhaus’ famous Ferrari P4/5 marked a turning point, in more ways than one. It was built in collaboration with Pininfarina as a sort of classically beautiful counterpart to the radically modern, Formula 1-inspired Enzo of 2002. It spawned a racing version, the P4/5 Competizione.

“We were racing P4/5 Competizione, which was originally badged as a Ferrari, at the Nürburging, and we got a call from a Ferrari lawyer. Now, in fairness to Luca, he probably knew nothing about this. But the guy said, ‘I see you on the internet, and you have Ferrari badges on the car. You owe us royalties.’ And I said to myself, this is boring me. So I took a screwdriver and I pried off the Ferrari badge. I hand-drew the Statue of Liberty torch and wrote ‘SCG’ and I stuck it on. Millions of people watched the video of this on YouTube. And that was basically the start of SCG.”

Glickenhaus maintains that there are no hard feelings between him and the Prancing Horse. Indeed, Ferrari now seems to consider P4/5 to be a part of its history (even if it presently insists that all special projects in its vein must now go through Maranello). Ultimately, however, he sees Ferrari as a company that has changed dramatically since the days when he rode his bicycle to Chinetti’s shop.

“I think it’s a mistake to say that there’s one definition of Ferrari,” he says. And he personally finds the Enzo era of the company most compelling. That’s when road cars, glorious as they were, were a means to support the construction of race cars.

In other words, he has the most appreciation for the time in which Ferrari was successfully doing what Glickenhaus is trying to do today.

On Glickenhaus Inc.

Speaking to the Glickenhauses, whether father James or son Jesse, it’s apparent how proud they are of their NHTSA small-volume manufacturer status. That’s why they’ve put so much attention into the vehicle ID plates, which bear a 17-digit VIN—proof to critics that this is a real operation building real, road-legal vehicles. It is probably as significant to them as any of the racing trophies they have earned.

“This is a solution to sell up to 325 cars a year,” James says of the small-volume status. “I’m not saying that we’re going to get above 325 cars per year, but with the Boot and the 004, we could. So we’re in the process of making those cars completely compliant with all safety requirements, everything that will be needed,” James says.

The Boot he mentions is their modern-day reinterpretation of Steve McQueen’s Baja Boot, also a part of the Glickenhaus collection. Last year, a team drove a Boot from California, where examples are currently made, to the starting line of the Baja 1000, ran the race, then drove home. They were nearly the last vehicle across the finish line, but they finished—an accomplishment in and of itself—and they beat the other contender in their class, Ford’s Bronco R, in the process.

In addition to the Boot, which will be offered in both two- and four-door configurations, and the aforementioned SCG 003, Glickenhaus is also working on the three-seat SCG 004. With its central driving position and available manual transmission, it’s a little like a modern-day McLaren F1; it will be offered in road-going form (004S), track-oriented but still road-legal form (004CS) or GT3/GTE-qualifying competition form (004C). It is not vaporware: At the time of writing, the prototype is undergoing endurance testing in Europe. A little further out is the SCG 006, a truly retro callback to the golden age of front-engine Italian GTs.

There is a certain common spirit that ties together these disparate vehicles. As Jesse explains it, in the not-too-distant future, “there may well be robotic taxis; cars for transportation might just exist as an app, a way to get from point A to point B. And then there will be cars for driving, which be like sailboats. We’re building the sailboats.

“People will be buying and driving our cars when they’re distilling their own ethanol fuel from potatoes in a cold storage locker—I mean, there are always going to be people who want to drive, and they’ll want to drive the Boot, or the 003 or the 004. That’s why the 004 is going to have a manual transmission.”

Can you build a viable, if boutique, long-term business model on the back of that notion? The Glickenhauses think so. Those of us who love to drive, and are not entirely sure about where the present path of electrification and digitization will lead, had better hope they’re right.

On Le Mans

There is one other car in the works, and it might be Glickenhaus’ most important one yet: SCG 007. If all goes according to plan, the 007 will race at the 24 Hours of Le Mans during the 2020/2021 FIA WEC season under the new top-level Le Mans Hypercar, or LMH, class. His goal is to win it outright.

Glickenhaus has had a seat at the table throughout the development of the LMH regulations; Jesse points out that the rulebook sketches out a car that looks an awful lot like the SCG 003. The overarching mission here is to make the top-level race cars look a lot more like real road-going vehicles than the impressive-yet-inaccessible LMP1 cars. It should open the door for more manufacturers and teams, making for better and more relevant competition.

Yet the implementation of this new class has been rocky, to put it lightly, and it is unclear who exactly Glickenhaus will be squaring off against at the Circuit de la Sarthe next year.

“We would love for other manufacturers to come in,” Glickenhaus says. “There are some so-called hypercar companies that have said, ‘We want to go racing!’ And we say bring it—that’s great. But I don’t think they understand the engineering challenge of going one lap on the ’Ring, let alone 24 hours, let alone a whole season of racing.”

Indeed, companies are already backing down from the challenge. Recently, Aston Martin pumped the brakes on its Valkyrie Le Mans Hypercar program. (“To be completely honest, I would be shocked if they managed to show up with that car for the first year,” Glickenhaus told me in 2019.) So it may well just be Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus and Toyota on the starting grid when the green flag waves in May 2021.

But, he assures me, they will be there. And more than the value a win might generate for the Glickenhaus brand, he understands the deeper significance of tackling the world’s revered races, whether it’s the Nürburgring 24 Hours, or Baja or Le Mans.

“It’s, one, to show that an individual can do it—and it’s not just me. I mean my family, it’s the crew, it’s the teams we work with. More than that, it’s that a small group of people are doing … well, perhaps it’s performance art. What we do is performance art. When you go to a race and see our fans, of course they want us to win. But they don’t really care. They love the fact that we’re there and we’re doing what we’re doing.”

This is about more than just the trophies. As with all the best racing stories, it’s about more than just the cars. Tied up in the image of America as an economic power are visions of big factories, of economies of scale, of industrial might. But there’s another side of our story—a nimbleness, an inventiveness, a DIY-ethos. That’s the kind of energy that fills the SCG shop, that seems to motivate James and Jesse and the crew that works for them. Just by earnestly engaging in the effort, they are proving that the spirit of Briggs Cunningham and Carroll Shelby lives on, demonstrating that the inventiveness of Jim Hall still matters.

Glickenhaus isn’t just talking the talk: He’s rolling up his sleeves and doing something about it. There’s nothing more quintessentially American than that. How could you not cheer him on?