My Autoweek colleague Murilee Martin has a semi-regular feature here on autoweek.com called “Project Car Hell.” The idea is to describe the agonizing, time-consuming, garage-space-gobbling, marriage-threatening project cars that look so appealingly simple and fun when you first acquire them but turn out to be endless, undying money sumps of Hades.

It’s not unlike relationships you may have had. At first, you see only the great possibilities, what can be, what you want to see. Your brain practices cognitive dissonance on any flaws that might be painfully obvious to everyone else. And, since you’re an adult now and you live in a free society, no one stops you, no matter how much you secretly, desperately wish they would.

Maybe I’m exaggerating.

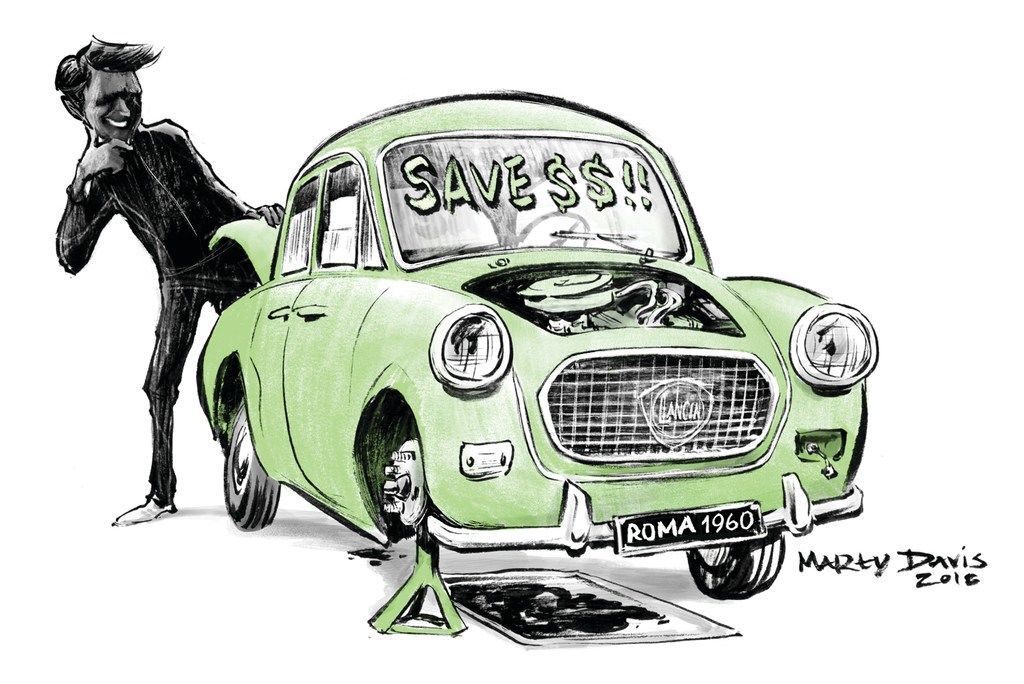

I had always wanted a Lancia Appia, the little Italian luxury family subcompact that was the peak of style for middle-class Romans 60 years ago. They looked cute, were loaded with clever engineering and were fun to drive. So when I spotted one at a quirky used car dealership two (or was it three?) years ago, with an asking price well below what I thought I’d have to pay, I pretty much had to buy it. The little 10-degree V4 had good compression in all four cylinders, the interior looked untouched, the exterior still had the sea-foam green of the lightest shade ever imagined. It had suicide doors and almost no rust.

Sure, it needed a complete right front brake assembly, with everything that goes with it, and it needed one of those cute little plunger-operated hand pumps that got oil to the sliding pillar front suspension, but those couldn’t be hard to come by, could they?

As Martin might say, “The hounds of Project Car Hell howled in derision.”

It was only a quick two years later that I got all the parts. Maybe one year. I only got them because the benevolent and kind-hearted president of the American Lancia Club, Steve Peterson, took pity on me. He loves Appias, too.

Now I am descending into the tortured psyche of the mechanical engineer who designed the brakes. The four individual wheel cylinders are done, rebuilt thanks to Peterson’s parts and because of the hard work and assistance of friends Aaron Robinson and Tom “Boost” Gage. Now all that’s left is to access the master cylinder, which Gage described as “a festival of poor accessibility.” Peterson said, “Yes, getting the master cylinder out is a true @#$%^* requiring long, thin, abnormally strong fingers with more joints than we were given, but with the proper expletives applied, it can be done.” And then that front suspension lube pump thing. And then flush everything and replace with new fluids. And grease all 27 Zerk fittings.

And then we should be good.

As I write this, I have two weeks to go before The Best of France and Italy car show Nov. 4 in Woodley Park, Van Nuys, sort of the Pebble Beach Concours for guys like me. In between now and then is some show in Las Vegas called SEMA, which might take up one of those weeks. Plus all the usual car-writing stuff. None of this seems impossible. Does it?

West Coast Editor MARK VAUGHN can be reached at mark.vaughn@hearst.com or on Twitter and Instagram @MVaughnAW