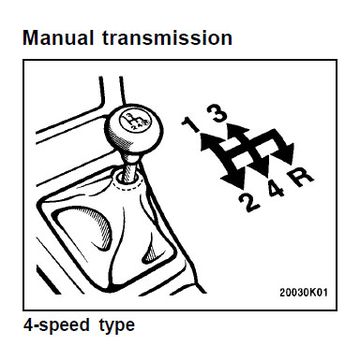

“What are you going to do with that?” ... “That” being a greasy Chrysler automatic transmission of indeterminate origin, sourced for free from a friend who wanted it out of his garage. And the answer, as my long-suffering wife, Bridget, well knew, was either “nothing” or “take it apart,” and most likely a combination of the two over the course of several years.

I split the difference: “I’m not sure yet.” She nodded, perhaps not thrilled but at least understanding. Car and house projects are my thing; she enjoys home improvement, too, but her hands-on joy is derived more from gardening.

I try not to question the rationality of fussing over tomato plants for six months when perfectly good tomatoes are sitting at the corner market any more than she questions the rationality of devoting hours of labor to the disassembly of a transmission for which we have no car.

At least not yet ...

Whether wrenching or gardening, painting or plumbing, it stems from a need to make something happen with the hands and mind. If you’re an avid DIYer, you know that immense satisfaction gained from learning how things work (or grow), how they go together and how to fix them when they break.

In my experience, the best way to understand how a mechanical component works is to take it apart piece by piece; touch the mechanism inside, the casting marks on the parts, the machining of the gears and valves and smell the decades-old lubricants. There’s simply no education like disassembly.

It’s the reassembly step that usually scares people away from DIY projects. The zen of how-to is a willingness to make mistakes, and when you’re talking about a multi-thousand-dollar investment like a car or a house, it can get tough to cross the threshold of fear. “Am I going to screw it up? Am I going to break it even worse?”

Maybe. Then you’ll do what you were going to do anyway: Call in someone who knows what they’re doing and write them a check. But you might fix it. You might save yourself some cash and gain a bit of self-confidence to tackle more projects. And I guarantee you’ll learn something about what to do (and what not to do) next time.

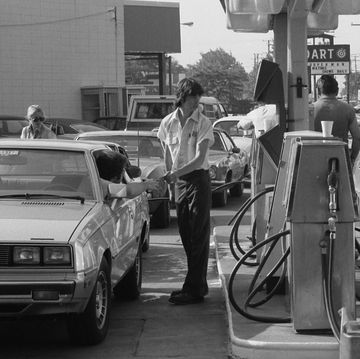

Case in point: I gained a priceless diagnostic lesson working on a friend’s ancient Dodge Dart in college. “It’s overheating,” he said. “Can you help me replace the water pump?” Sure I could, figuring it couldn’t be that difficult, and after six hours of sweating in the dorm parking lot, I had actually completed the job. My friend fired it up, let it run for a few minutes, then sighed, dejected. “It’s still overheating.”

There were no leaks, and the radiator top hose was hot, indicating a working thermostat. Suspicious, I finally looked at the dash and saw the temp gauge reading perfectly between H and C. Upon further questioning, it became apparent the gauge had been faulty for years, remaining on C; when it randomly began working again (indicating a perfectly functioning cooling system), my friend, who’d never seen the needle budge off C, assumed the Dart was overheating.

The Dart was fine. Granted, it had been fine before we started, but I was able to add “Slant-6 water pump” to my slowly growing skill set. More importantly, I learned to verify a problem before beginning work. Experiences since have taught that, even if the Dart had been overheating, I should have started by testing the thermostat, checking for a collapsing lower hose and other less invasive potential causes before swapping the water pump.

Of course, if you’re just taking something apart for the sake of exploration, as with my stray automatic transmission, there’s no diagnosis necessary. Nor is there any fear of making a problem worse; it’s simply the pure joy of disassembly and discovery. Just don’t forget to take a break and help weed the garden, too.

Digital Editor ANDREW STOY can be reached at andy.stoy@hearst.com or on Twitter @andrewstoy